What was that bang?

At first it seemed like Bee-bee had just overheated and popped the top off the expansion bottle. We let her cool down and refilled the radiator. We tried to start the car but got nothing but a ‘clunk’. Andy thought the starter motor might be jammed, we rocked Bee-bee backwards and forwards (for sympathy and to hopefully un-jam the starter motor). A turn of the key and she sprang back to life in a huge cloud of white smoke. It was at this point that Andy declared that we’d probably blown the cylinder head and that water had leaked into one of the cylinders which became ‘hydrolocked’. We sloped on cautiously towards the next town in a cloud of white smoke. Stuck in Kumluca

Frantically searching the Hilux Surf forum for advice on what he suspected, Andy declared he was “95% sure the Head gasket had blown”. Aside from a crash, this was one of the worst things that could happen to our car (mechanically and financially). We had 48 hours to get us and a broken car 301.43 miles (485.10 km) to the Port of Tasucu where a non-refundable ferry was due to take us to Cyprus. As with every tragedy there are the heroes and villains; our hero was Alim the hotel manager’s son who spoke English, understood our predicament and arranged for some tow truck people to come in the morning. The unfortunate villain was the waiter in the restaurant who informed me they didn’t serve alcohol. Tow Truck (Wheelin' and Dealin')

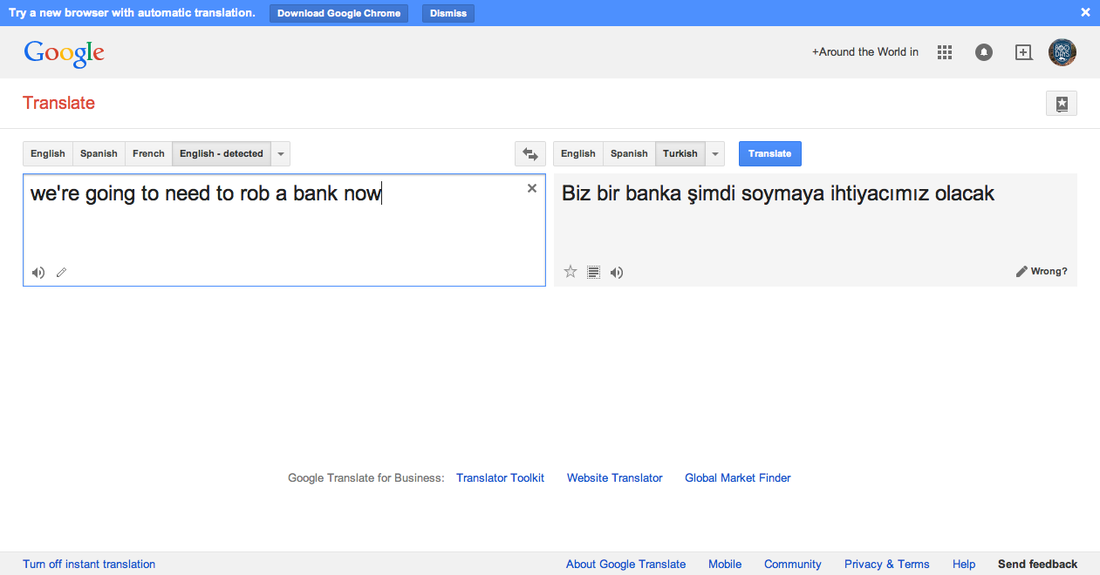

The final computer translation told them we were off to rob a bank. Ironically, when Alim took us to the cash point I sat in the back with a shotgun under my feet. I assume that was a normal item in a car here and he understood we were joking about the bank. I didn’t mention it. Tow Truck 1 - Ugel the Rally Driver

Tow Truck 2 - Mustafa the Redbull Racer

We spent about 2 hours in a smoky (but warm) station office with a Turkish soap opera on TV in the corner. A car of oily youths arrived with a few ‘new’ alternator options and scrambled about systematically until the truck roared into life again. Mustafa necked 2 cans of Redbull. We were off. We Drove All Night

17 Hours in Tasucu Port

We walked back into town (not daring to ask for a lift). During this time we must have set a local record for number of teas drank. We were exhausted and cold, we rooted at a friendly local café, ordering small dishes with lengthy interims to justify our temporary residence at their table. When it eventually went dark we bussed our way back to the Port but were stopped at the customs gate where we spent another hour dozing in chairs with bored customs officials in their office. Eventually they let us have access to Bee-bee (if we ran through the port and no one saw us). We popped the tent subtly, sandwiched between rows of lorries and lay down for an hour. All Aboard The Lady Su

Crossing the Cilician Sea

He beckoned us over to come up so we made our way through the ships corridors, stepping over piles of broken furniture and tools, up onto the ships bridge. Muhammed, the lone Captain, seemed to appreciate our company up on the bridge- he gave us bananas and told us that the boat had to be registered in Sierra Leone as it would never have passed strict Turkish health and safety regulations. Docking in Girne

Across Aphrodites' Island

The DiagnosisThe devastating news was what we expected; the cylinder head was cracked in two places.

1 Comment

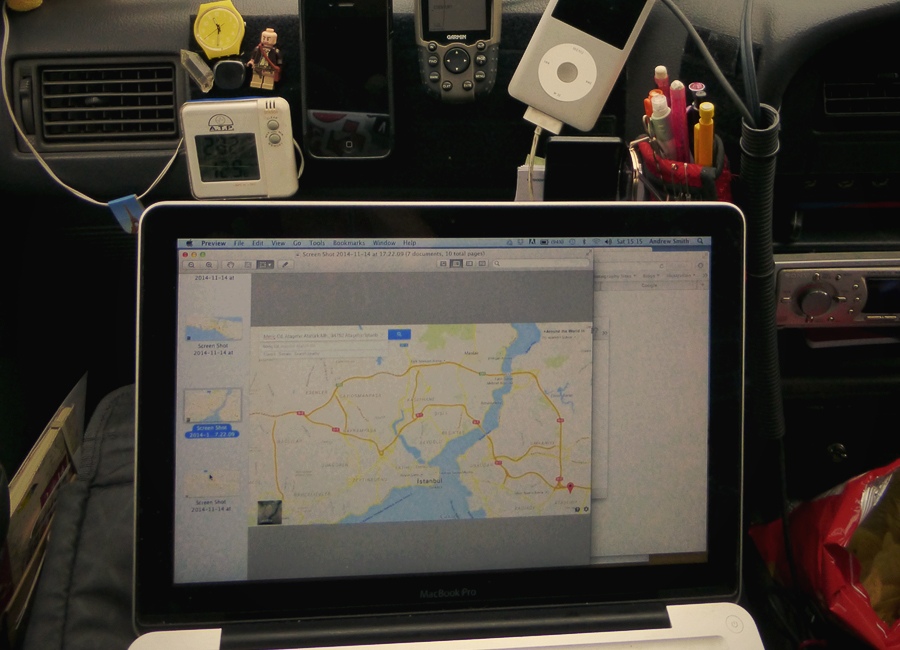

Geographically it is obvious why Istanbul, with its 14 million people, is considered the second most congested city in the world. The narrow 30km stretch of land, where Istanbul sits, is the central corridor linking Europe to Asia: it is also divided by the Bosphorus Strait, linking the Black Sea in the North with the Sea of Marmara in the South. Just two bridges span the strait linking Europe to Asia, forming two of the most hectic bottlenecks in the world. More than 116 million cars travel across the bridges every year on just 14 lanes.

You drive on the right (most of the time), beep your horn… a lot, ignore traffic lights and road signs and, generally, do what you want. People often drive without lights in the dark and no-one uses indicators. If all that wasn’t enough - It’s not only the drivers you have to worry about, pedestrians also think they have the right to step out into the road at anytime, normally without looking! Our introduction to Istanbul involved driving onto Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge where 14 tollbooth lanes merge magically into just 5 east-bound lanes. Here, street vendors take advantage of the slow moving traffic to peddle their wares. This involves standing in the middle of the highway, usually with a large wooden cart, as rows of traffic pass dangerously close on either side. If the traffic clears and speeds up the vendors attempt to dive back onto the ‘not-much-safer’ hard shoulder. The vendors work well into the twilight hours and are not aware of how much a hi-vis jacket might extend their life expectancy. Just to put all this information into context it took us 4 hours to drive just 16km across the city. For the remainder of our 6-day visit we decided to park up Bee-bee and use public transport. Although public transport was lengthy and crowded (with 5 million users daily), it was cheap, varied and certainly less stressful than driving ourselves around the city. Thousands of ‘Dolmus’ minibuses interweave their haphazard way across the vast expanse of suburbs. Jump on-board and pass your bargain fare to the driver via a chain gang of squashed passengers. The Dolmus drivers are possibly some of the worst in the city, but as a passenger you benefit from their skilled overtaking, brazen manoeuvres and knowledgeable shortcuts.

Metrobuses interweave the city’s streets, linking suburban overland trains with a network of modern tramways. For a more nostalgic tram journey, you can catch the restored trams which climb the huge pedestrian Istiklal Caddesi Street in Beyoğlu. Too tired/lazy to climb the steep hill from the Bosphorus up to Taksim Square? Try the Funicular ‘climbing train’ which transports you the 60 metre ascent in just 110 seconds. A pre-paid travel card is swiped for each trip, regardless of the transport method, with each journey only costing a few lira.

While we mainly explored the city by foot, the variety of fascinating ways of getting around in Istanbul, with a wonderful mix of passengers, only added to our new-found love of the city. Greece is a huge country criss-crossed with a gravel road network of unpaved tracks covering 75,603km. 4x4 is by far the best way to discover some of its outstanding beauty and with a little planning you can hunker down behind the wheel and pretty much cross its entirety without using a paved road. This network of roads is in constant need of repair and in the mountains landslides are common. Most of the driving is fairly moderate and unlikely to push your skills (or vehicle) to the limit. The occasional unexpected rainstorm can make conditions more challenging (fun) but generally most routes are drivable throughout the whole year (with the exception of some mountain areas). The main reason for taking these routes is not solely for the driving, with just 11 million (compared to 64 million in the UK) people living in Greece you can experience some exceptional wild areas in relative solitude. Shamefully, new roads continue to be constructed with no respect for the natural environment. Our first experience of Greece green-laning was a route from Arta to the Meteora, the main stretch of which followed the Acheloos River valley South-east of Mount Tzoumerka. Just like the other mountains of the Pindus range, the area is home to rare mammals like bears and wolves - although they tend to keep safe distances from human intruders. Sadly nearly 80 years after it was first proposed, the massively controversial greater Acheloos diversion scheme is well under way and has pretty much ruined the natural beauty of the area. Firs, black pines, maples and other trees envelop the road creating a riotous canopy of reds, yellows and greens; thankfully obscuring the atrocity of the river diversion scheme. Our next off-road route looked like a scenic two-hour diversion on our rather ineffective 1:425.000 scale map. From the small village of Pouri, just north of Mount Pelion, we would take the ‘scenic’ green route down to the coast then head west towards Kerasia, just 16km away. Having tried two alternative trails and deciding they were not ‘the one’ marked on our ‘map’ we stopped at the head of a third to ask for directions (N39°28’59.525” E23°5’50.226”). With our token gesture of a map in hand and some pretty flamboyant gesticulating we questioned two old locals if we could get through to Kerasia. In typically Greek style they entered into an animated debate before offering a relatively convoluted answer. We think the gist of which was that we could but the road was so bad we shouldn’t – we pointed at Bee-bee and shrugged our shoulders, at which point, they both shrugged their shoulders and walked off. Kerasia was only 16km away, if the road was too bad or blocked we’d just turnaround and drive back, right? Two days later we emerged in Kerasia, muddied, tired, low on fuel but buzzing from our off-course off-roading. Our two-day adventure began when we decided to ignore the advice of the locals and drove off downhill towards the coast. The track was rutted and well used. We passed a few local working 4x4’s coming the other direction, the drivers all smiled politely and waved back at us as we pulled over to let them pass. After a slow winding 600m descent with some stunning views we arrived at sea level at a tiny fishing bay (N39°30’23.725” E23°4’47.385”). An immaculate little fisherman’s church on the bank of a small river poignantly marked the end of the well-used track and offered a potential safe haven to travellers wishing to venture beyond. We stopped for an opportune picnic before continuing into the unknown. The track continued up the other side of the valley and from this point became muddier, rougher and at times much steeper than we had experienced on our descent. Thankfully the ominous black clouds held off until we reached the summit. After a fairly slow 950m ascent, using instinct and a compass at every junction, we found ourselves at the top of a wooded plateau on the northern part of the Pelion Range. Once we’d reached the highland it became apparently clear that the tracks here were used by logging trucks, unfortunately the heavy traffic (weight not frequency) meant the tracks were much muddier. After 5 hours driving, the afternoon turned to evening and it became apparent we weren’t going to make it to Kerasia before nightfall. We found a clearing in the woods and set up camp. Two hours after we’d gone to bed we were woken by two cars approaching through the forest. Two 4x4’s pulled up alongside our camp and a Greek family of 7 promptly exited the vehicles and approached our camp. Much to our surprise, it turns out we were not the only ones who were lost on the mountain. The family were attempting to complete the same journey as us but in the opposite direction. We exchanged information about the road ahead; we were relieved to discover Kerasia was just 2 hours away.

In a twist of irony we told the family the same advice we received at the start of our journey; you could get through but the road was so bad you probably shouldn’t, we also told them Pouri was about 5 hours away… They shrugged their shoulders in disbelief and carried on regardless. At sunrise our dark, foggy camp became a beautiful, autumnal woodland haven. We set off and completed the last few muddy miles, re-joining the tarmac for a spectacular descent from the mountains and back to the coast.

Our tasting travels of the Balkans; unlikely to want to eat pastry for a while again but overall a unique culinary experience of the regions cheap eats. Who needs fine dining and fancy restaurants when the real specialities of new countries are found in stalls, takeaways, markets and roadside cafes.

Back in 2012 we visited the National Centre for Contemporary Art in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, where we watched a film by Anri Sala called ‘Dammi I Colori’. This intriguing film documented former artist and Mayor of Tirana Edi Rama’s controversial project to inject a riotous array of colour into the countries Communist era buildings. Naively we knew very little else about Albania. In the film Tirana looked horrifically run down, incredibly depressing and fairly dangerous - leaving Emma and I with the feeling that it should be avoided. Fast forward 2 years and we find ourselves at the Albanian border extremely excited at the prospect of visiting Tirana. During early 2014 I began to read more about Albania as it became a potential stop on our new route. The countries recent history was fascinating. After the Second World War the country became a Socialist Republic and was ruled from 1944, until his death in 1985, by Enver Hoxha. What was so shocking was Albania's self-isolationist policy and how it managed to exist in Europe during this period. The Communist model borrowed from the Russians led to a political allegiance that was superseded in 1960 when the Russians demanded that a submarine base be set-up in Albanian territory. Bizarrely, Albania realigned itself towards Maoist China and the country experienced a Chinese-style cultural revolution; older administrators were transferred to remote areas and younger trainees placed in positions of power. The introduction of Collective Farming and a total ban on organised religion was also enforced. The repressive political stance meant that tyrannical laws were enforced, people lived in fear of the secret police and private car ownership was banned. Until 1991 the total number of cars in Albania was only around 6000. Now the number of cars in the capital alone has increased to over 300,000 (3 in every 5 are stolen Mercedes from Western Europe). When chairman Mao died in 1976 Albania’s unique relationship with China came to an end and the country was left completely isolated. The economy was left in tatters and food shortages became common. The transitional period between Hoxha’s death in 1985 and the countries rebirth in 2000 saw much turmoil. The fall of communism in Albania, the last such event in Europe outside the USSR, started in December 1990 with student demonstrations. During this time most Albanians were unaware that the Berlin Wall had fallen the previous year! During the Balkans war in the mid-1990s, Tirana experienced dramatic events such as the Albanian Rebellion that unfolded in 1997. The unrest was kick-started by failing fraudulent pyramid investment schemes endorsed by corrupt government officials. Eventually the country descended into national civil disorder and violence resulting in 2000 deaths and the government being toppled. In 2000 Edi Rama became the mayor of Tirana. Rama entered office facing the challenges of corruption, a lack of citizen support, lawlessness and a miniscule budget. He also had the added pressure of working with European Union officials in the lead-up to Albania’s application to join the EU. Rama, a former artist, national basketball player and writer began his term by implementing his ‘Clean and Green’ and ‘Return to Identity’ projects. Rama’s deceptively simple plan to cut crime, curb corruption and win the people over was completely unique. The aim of Rama’s ‘Clean and Green’ project was to unite the residents of Tirana and to instill civic pride and a sense of security back to the city’s inhabitants. He planned to achieve this by reclaiming public spaces, demolishing illegal buildings around the River Lana and transforming the grey ‘Communist’ city into Europe’s most colourful capital. Rama’s first step in reclaiming ownership of the city for the people was to paint the drab grey Communist concrete facades in vibrant colours and geometric patterns. This simple injection of colour became a focal point and the people reacted with discussion. Despite split opinions, is was the first time there was a sense of a shared public space and community. "After communism and the events in 1997 people were lacking a sense of belonging to the country. There was a rage against everything that was a state building because it was perceived as property of the enemy… We are trying to make people understand that what is public is also yours." Edi Rama quoted in "You've got to tear this old building down" Throughout the 90’s hundreds of illegal kiosks and apartment buildings were constructed without planning on former public areas. Rama’s projects reclaimed public space by demolishing illegal buildings, which resulted in the production of 96,700 square metres of green land and parks. Within these spaces Rama planted nearly 55,000 trees, punctuating the grey of the city with lush green public areas. The simple act of painting and planting wasn’t just an aesthetic change, it was a political act, which prompted social transformation and much debate. This simple rebirth and the signs of change revived the hope of the people by making them proud of their environment; crime fell, people dropped less litter and eventually a collective responsibility crept into peoples consciousness. This painterly transformation didn’t resolve all the cities problems but it did begin to put the people first, it showed the citizens that they could have faith in their leaders once more. Despite the capitals development, Rama’s progressive efforts are not entirely understood or appreciated throughout the whole of Albania. Rama’s dramatic transformation of Tirana did however give birth to a rare breed of Balkan politician – one that drew positive interest from Western audiences. His Twitter, Facebook and TED Talk internet presence make him a PR dream, this coupled with his proven track record meant he landed the country’s top executive position, prime minister, in 2013. He now faces the challenge of shifting the West’s perception of the country. Some critics (mostly Rama’s political opposition) say that the facade of new Tirana is just that, a facade. Albania is still Europe’s poorest country and is plagued by drugs and arms trade, power-cuts, murders, corruption and organised crime. It may be true that not all of Albania’s ingrained problems can be solved with a lick of paint but it is certainly a good start in lifting Albania from its historical abyss. Rama’s legacy and vibrant attitude has had, and continues to have, a lasting effect on the country. New buildings are equally as colourful as the old and not only has he restored civic pride, he has inadvertently created cultural tourism to help the countries economy. Albania completely fulfilled all my expectations and I can confirm that Edi Rama fulfilled his goal of creating the most colourful capital in Europe. "Tirana has become the good news from Albania and has changed the image of the country. People that come here are surely surprised, because the stereotype is very strong, and is very different from the reality. And it's nice to see foreigners coming and being amazed, just amazed." Edi Rama quoted in "You've got to tear this old building down" |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed