|

Gaze at the constant stream of romantic overland expedition posts on social media and it’s easy to believe that it’s all exotic sunsets, idyllic camp spots and laughter with locals. In reality however, it’s not all thrilling and fulfilling- overlanding has more than its fair share of exasperations and frustrations. But surely that’s part of the experience, right? Most days these provocations can be shrugged off, even laughed at, but even with the strongly developed tolerance and patience of an overlander sometimes these few repeating niggles make you want to scream from the roof(tent)tops. In this short series of blogs I retain the right to rant, expose the things that have left nail marks in the steering wheel and detail our main adventure annoyances, our overlanding irritations. So here is my stage on which to vent. First up, bad roads. Expected? Yes. Tolerated? Mostly… We’ve experienced some pretty terrible roads on our travels. Just to clarify, we’re not talking about off-road dirt tracks high up into the mountains here, we’re talking about main roads, motorways and city streets. Russia, Kosovo, Albania, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan all have their fair share of ‘bad’ roads often with potholes larger than your car. Deep chasms are not the only surface danger, due to heavy truck traffic many roads become furrowed, once in a groove your vehicle handles like it is on rails, without a vigilant steering wheel wrestle this can suddenly send you veering towards oncoming traffic. Travelling in Armenia in your own vehicle is costly, on entry we paid at least £50 for ecology and road tax. Ironically when we left we should have billed Armenia for the damage done to our car for using such terrible roads. I’m not sure where the tax money is going but it certainly isn’t being spent on the roads. The highway system in Armenia consists of 7,633km of (apparently) paved roads, of which, 1,561km are supposedly expressways; our average speed on Armenia’s M1 was about 28mph. One of the worst stretches of urban street we encountered was in Sevan; some of the potholes on the main high street are so large you can see them on Google Earth! It is not just the road surfaces that are dangerous in these countries; the lack of road markings, signals and ambiguous road junctions are equally hazardous, as are open drain covers and deep gutters. Other potential dangers include animals, overloaded trucks and clueless pedestrians. In Georgia we narrowly avoided hitting a child, who crossing the road with his mother, ran straight out in front of our vehicle. Fortunately the only physical damage done to him was from the heavy clout round the ear his mother gave him for being so careless. Georgia’s excessive use of speed bumps is simply annoying. A motorway should never have speed bumps! Especially unmarked speed bumps.

In Western Europe we have a system for using roundabouts, it works because every roundabout employs the same system, you know your place and everybody else knows theirs. In Eastern Europe the system fails as every roundabout operates a different system. Some roundabouts allow vehicles that are approaching to have right-of-way whilst others allow the vehicles on the roundabout to have priority, some even employ both on the same roundabout. Some roundabouts even have traffic lights mid-roundabout whilst others have no road markings at all and are simply a massive city square with six lanes of traffic and a fountain in the middle. So, bad roads, the first of my adventure annoyances- the logistical network allowing me to traverse this wonderful planet, but at times my reason for breaking the 6pm G&T rule.

2 Comments

Our tasting travels of the Balkans; unlikely to want to eat pastry for a while again but overall a unique culinary experience of the regions cheap eats. Who needs fine dining and fancy restaurants when the real specialities of new countries are found in stalls, takeaways, markets and roadside cafes.

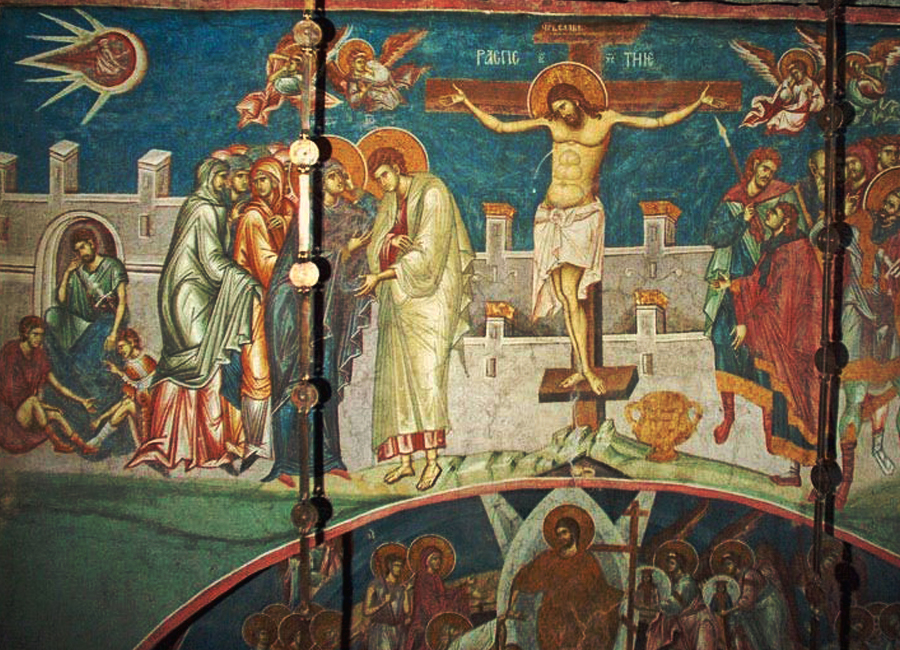

Two worlds of war and peace are forced together in Western Kosovo where a 700-year old Serbian Orthodox Christian monastery quietly nestles amongst chestnut groves in a mountain valley. The approaching road displays evidence that racial tensions still exist here- Serbian Latin writing on every road sign has been scrawled over with paint. We were heading for Deçan not Dečani. This was the first religious site we have visited where we had to drive through checkpoints, around roadblocks and submit our passports to gun-wielding military before entering. Visoki Decani Monastery has been described as "the largest and best-preserved medieval church in the entire Balkans" with several thousand Byzantine frescoes adorning the interior walls. The paintings took 6 groups of artists ten years to complete and cover an area of 4,000m2. 25 monks live within its heavily guarded walls, although the last direct attack was grenades in 2007, the threat of ethnic violence remains.

I have never seen Andy’s jaw drop as it did as we entered the church, stepping across the original marble floor at the foot of angular, stone columns. The frescoes greet you like a window from the past, where several thousand Byzantine paintings depicting 1,000 portraits of Saints stare silently from all sides. Their intricate, colourful detail cover almost the entire interior of the church. Uniquely, the religious depictions include the only existing image of Jesus with a sword, Petar clarified “this is a spiritual sword, representing the Word of God, in which the sword is cutting sins”. Nearby, on the ‘Crucifixion’ fresco we noticed what many people believe to be two UFO’s with men inside. “Not so” Petar smiled “in Byzantine iconography, these two ’comets’ represent the sun and the moon, and a man inside is the personification of the heavenly body of the sun and moon” We felt incredibly privileged to have such a personal, knowledgeable insight. “Can you identify all of the frescoes inside here?” I asked him “After 13 years… almost” he replied humbly. The Monastery was established in 1327 under the instruction of Serbian Medieval King St. Stephen of Decani. The monastery is both his life’s work and his mausoleum; his 684 year-old body remains in a coffin at the head of the altar. Petar informed us that 10 years after his funeral, the body of St Stephen was found intact in his grave, perfectly preserved and undecomposed, with a sweet smell which exists until today. “We do nothing to preserve the body, it is forbidden in the Orthodox Church to do anything with a human body after death- we don’t even know any technique to do it! We have no interest to preserve the body, because this is not an important factor when considering someone as Holy”. Petar explained “The body is still whole and fragrant, even when constantly exposed to air and kissing. We believe this is because God’s energies are still present in it.” Every Thursday, the coffin is opened to allow worshippers to show respect, say prayers and offer Thanks to St Stephen. Petar invited us to join them for this service in 5 days but, with people awaiting our arrival in Montenegro, we regrettably declined the offer. We were however, fortunate enough to accept his invitation to join them for their evening worship.

The feeling that so much had changed outside of these walls in the last 700 years, yet inside the marble walls the rituals, words and music were untouched by time. The candlelight flickered the walls, making the gold tinged frescoes glimmer- our eyes were seeing exactly what worshipers saw 700 years previously. The heavy smoke swung from incense thuribles. Ceremonial devotion frozen in time.

I asked Petar what he hoped for the future of the Monastery; “We hope it will survive because it is under God’s protection. He has preserved the Monastery during seven centuries under very difficult circumstances. We are determined to stay and live here no matter what happens, trying to have love also with our enemies”. |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed