|

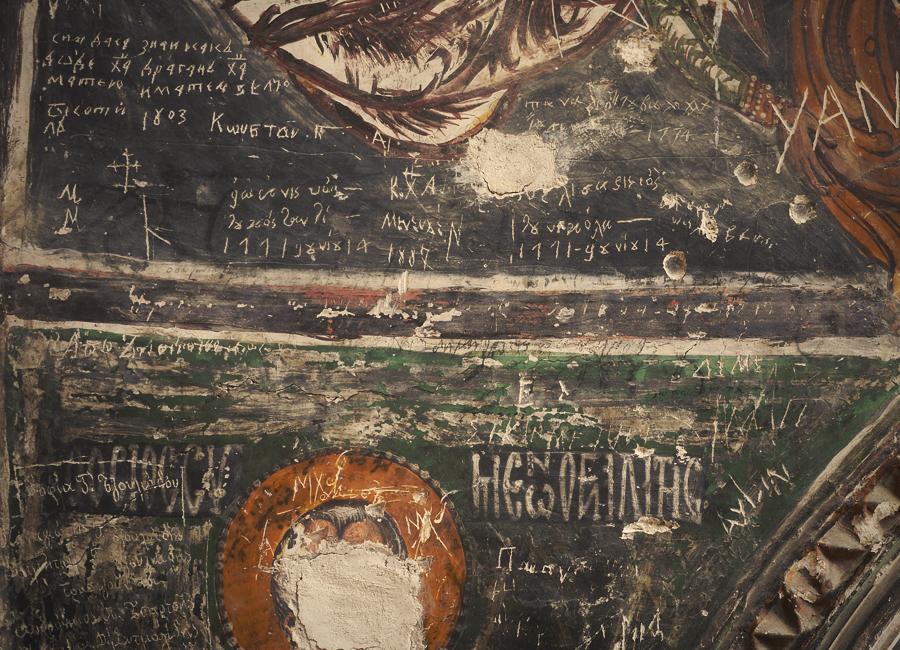

Clinging to a rock face, nestled high up on a steep cliff in the Pontic Mountains in the Altındere National Park, Turkey, is the 4th century Sumela Monastery; a site of great historical and cultural significance. Having already visited the Monastery of Ostrog (Montenegro) and the spectacular Metéora complex of Greek Orthodox monasteries, both of which are perched precariously in isolated places, we were aware of the tradition typical of inaccessible Monasteries throughout the region. The remoteness of such sites meant that the monks were often safe from invaders; they believed the altitude bought them closer to god and the servitude involved in the construction of such remote structures surely secured them a seat in heaven? With such solitude these beautiful locations are highly conducive to prayer, contemplation and meditation. They became the focus of pilgrimage; a place to turn your mind away from the distractions of the outer world and focus on discovering the profound truths of the inner world. For over 1,629 years a monastery of some description has endured the elements on this secluded spot in Northern Turkey 1,200 metres up. During its long history the monastery has fallen into disrepair several times, then consequently restored by various emperors throughout the ages. It was around the 13th century that this existing incarnation (including the frescoes) was formed during the reign of Alexios III. During the Ottoman Empire the monastery was granted the sultan's protection and given rights and privileges that were renewed by following sultans protecting it for many decades. During the 1916-18 occupation of Trabzon the monastery was seized by the Russian Empire, then in 1923 the site was abandoned during the Turkish War of Independence. Today the monastery is open as a tourist attraction; despite its cultural and religious significance the site draws in curious visitors who marvel at its location alone. Unlike the perfect frescoes we witnessed at Decani monastery, the frescoes here have endured years of weathering, as well as vandalism during the times that the monastery was abandoned. At first glance the vandalism my seem unthinkably sacrilegious but on closer inspection un-digestible layers of scratchy scrawl engraved on the surface reveal a fascinating insight into the monasteries history. Who was Nebile Okur and what was he doing here in 1970? But it’s not just modern day graffiti, look a little harder and you’ll notice earlier and earlier dates; 1964, 1952, 1911, 1899, 1878, 1833, 1803, 1774, 1762 and the earliest we spotted 1511. The names and dates here document the times that are often unaccounted for by the history books. Like many of the Frescoes in the Göreme cave churches we visited in Cappadocia the eyes and faces on the paintings have vanished. It is said that the eyes are often worn due to pilgrims touching them. Some say that the faces were often chipped off by people wanting to keep a souvenir of their visit. The frescoes of the chapel were painted during different periods; in places the newer layer has been completely removed or fallen off revealing the previous frescoe which has been systematically chipped for the new layer of plaster to adhere to. Sumela monastery is a marvel from both outside and in; externally, the sheer devotion of its construction and breathtaking position in the landscape. Internally, within the crumbling and restored walls, echo stories over the millennia of prayer, devoutness, safety, war, sacrifice and a restored feeling of peace and optimism for the future.

1 Comment

It was a cold, grey, drizzly day in Niksar, Turkey but as the door to the household kitchen swung open we were met with two kinds of warmth; that of the wood burning stove blazing in the corner and the welcome friendliness of a Turkish family. Having met our campsite owner, Tunay, only the previous day he had proudly embraced the visitors to his home town and invited us to eat with his family the following day. As is often the way with home-cooking, the mix of dishes was delectably different from the occasional kebab street-eat we had sampled so far across Turkey. ‘Çay’ is the staple throughout the day- black tea sipped from small, tulip-shaped glasses with plenty of sugar. The tea kept flowing, topped up from a double teapot on the stove; strong black tea from one spout and hot water from the other.

We frequently encounter such hospitality, warmth and openness from people in foreign lands, an unforgettable experience and fond, lasting memory.

What was that bang?

At first it seemed like Bee-bee had just overheated and popped the top off the expansion bottle. We let her cool down and refilled the radiator. We tried to start the car but got nothing but a ‘clunk’. Andy thought the starter motor might be jammed, we rocked Bee-bee backwards and forwards (for sympathy and to hopefully un-jam the starter motor). A turn of the key and she sprang back to life in a huge cloud of white smoke. It was at this point that Andy declared that we’d probably blown the cylinder head and that water had leaked into one of the cylinders which became ‘hydrolocked’. We sloped on cautiously towards the next town in a cloud of white smoke. Stuck in Kumluca

Frantically searching the Hilux Surf forum for advice on what he suspected, Andy declared he was “95% sure the Head gasket had blown”. Aside from a crash, this was one of the worst things that could happen to our car (mechanically and financially). We had 48 hours to get us and a broken car 301.43 miles (485.10 km) to the Port of Tasucu where a non-refundable ferry was due to take us to Cyprus. As with every tragedy there are the heroes and villains; our hero was Alim the hotel manager’s son who spoke English, understood our predicament and arranged for some tow truck people to come in the morning. The unfortunate villain was the waiter in the restaurant who informed me they didn’t serve alcohol. Tow Truck (Wheelin' and Dealin')

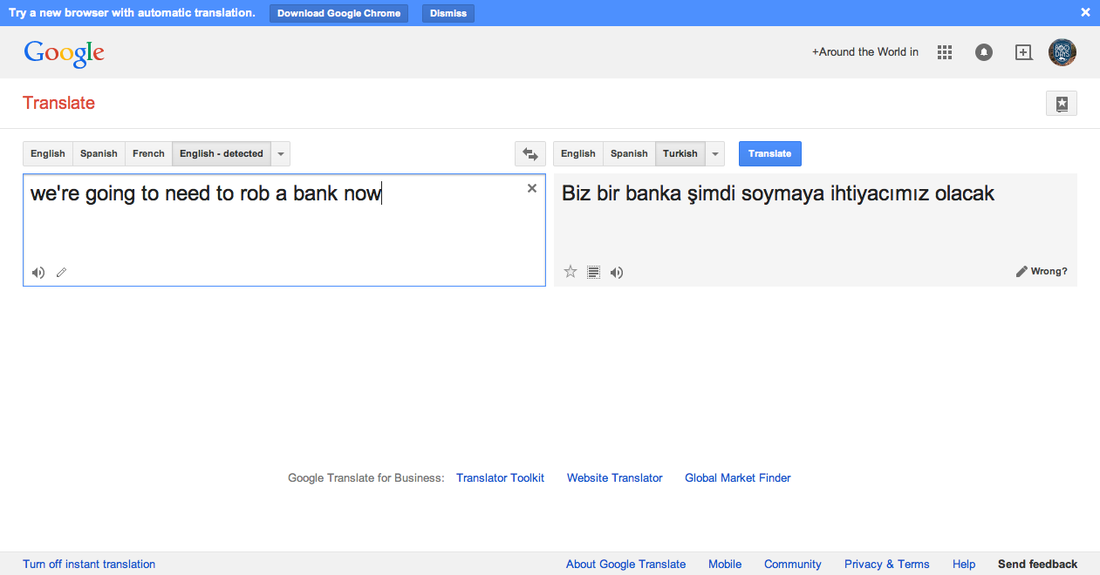

The final computer translation told them we were off to rob a bank. Ironically, when Alim took us to the cash point I sat in the back with a shotgun under my feet. I assume that was a normal item in a car here and he understood we were joking about the bank. I didn’t mention it. Tow Truck 1 - Ugel the Rally Driver

Tow Truck 2 - Mustafa the Redbull Racer

We spent about 2 hours in a smoky (but warm) station office with a Turkish soap opera on TV in the corner. A car of oily youths arrived with a few ‘new’ alternator options and scrambled about systematically until the truck roared into life again. Mustafa necked 2 cans of Redbull. We were off. We Drove All Night

17 Hours in Tasucu Port

We walked back into town (not daring to ask for a lift). During this time we must have set a local record for number of teas drank. We were exhausted and cold, we rooted at a friendly local café, ordering small dishes with lengthy interims to justify our temporary residence at their table. When it eventually went dark we bussed our way back to the Port but were stopped at the customs gate where we spent another hour dozing in chairs with bored customs officials in their office. Eventually they let us have access to Bee-bee (if we ran through the port and no one saw us). We popped the tent subtly, sandwiched between rows of lorries and lay down for an hour. All Aboard The Lady Su

Crossing the Cilician Sea

He beckoned us over to come up so we made our way through the ships corridors, stepping over piles of broken furniture and tools, up onto the ships bridge. Muhammed, the lone Captain, seemed to appreciate our company up on the bridge- he gave us bananas and told us that the boat had to be registered in Sierra Leone as it would never have passed strict Turkish health and safety regulations. Docking in Girne

Across Aphrodites' Island

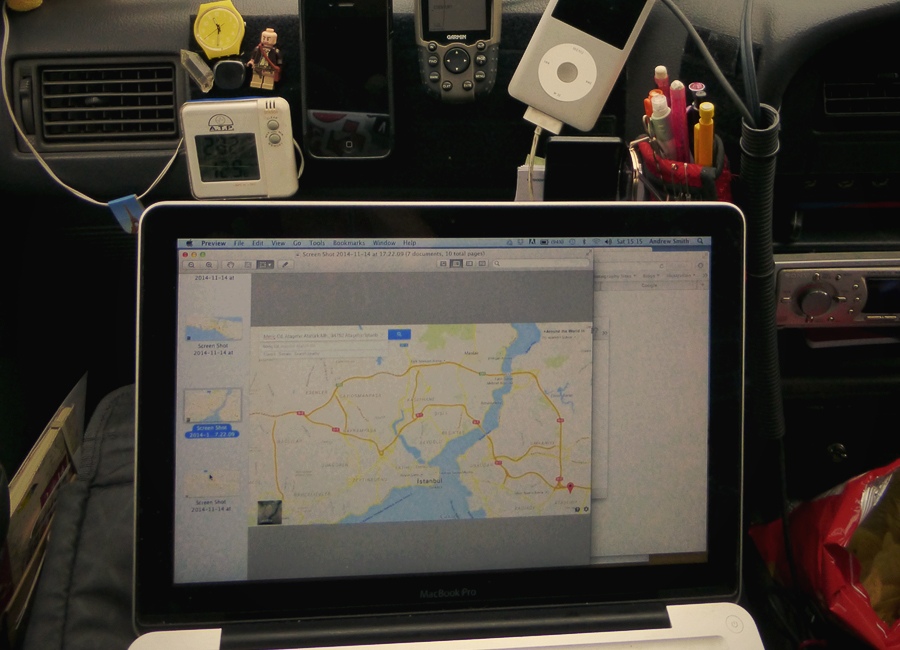

The DiagnosisThe devastating news was what we expected; the cylinder head was cracked in two places. Geographically it is obvious why Istanbul, with its 14 million people, is considered the second most congested city in the world. The narrow 30km stretch of land, where Istanbul sits, is the central corridor linking Europe to Asia: it is also divided by the Bosphorus Strait, linking the Black Sea in the North with the Sea of Marmara in the South. Just two bridges span the strait linking Europe to Asia, forming two of the most hectic bottlenecks in the world. More than 116 million cars travel across the bridges every year on just 14 lanes.

You drive on the right (most of the time), beep your horn… a lot, ignore traffic lights and road signs and, generally, do what you want. People often drive without lights in the dark and no-one uses indicators. If all that wasn’t enough - It’s not only the drivers you have to worry about, pedestrians also think they have the right to step out into the road at anytime, normally without looking! Our introduction to Istanbul involved driving onto Fatih Sultan Mehmet Bridge where 14 tollbooth lanes merge magically into just 5 east-bound lanes. Here, street vendors take advantage of the slow moving traffic to peddle their wares. This involves standing in the middle of the highway, usually with a large wooden cart, as rows of traffic pass dangerously close on either side. If the traffic clears and speeds up the vendors attempt to dive back onto the ‘not-much-safer’ hard shoulder. The vendors work well into the twilight hours and are not aware of how much a hi-vis jacket might extend their life expectancy. Just to put all this information into context it took us 4 hours to drive just 16km across the city. For the remainder of our 6-day visit we decided to park up Bee-bee and use public transport. Although public transport was lengthy and crowded (with 5 million users daily), it was cheap, varied and certainly less stressful than driving ourselves around the city. Thousands of ‘Dolmus’ minibuses interweave their haphazard way across the vast expanse of suburbs. Jump on-board and pass your bargain fare to the driver via a chain gang of squashed passengers. The Dolmus drivers are possibly some of the worst in the city, but as a passenger you benefit from their skilled overtaking, brazen manoeuvres and knowledgeable shortcuts.

Metrobuses interweave the city’s streets, linking suburban overland trains with a network of modern tramways. For a more nostalgic tram journey, you can catch the restored trams which climb the huge pedestrian Istiklal Caddesi Street in Beyoğlu. Too tired/lazy to climb the steep hill from the Bosphorus up to Taksim Square? Try the Funicular ‘climbing train’ which transports you the 60 metre ascent in just 110 seconds. A pre-paid travel card is swiped for each trip, regardless of the transport method, with each journey only costing a few lira.

While we mainly explored the city by foot, the variety of fascinating ways of getting around in Istanbul, with a wonderful mix of passengers, only added to our new-found love of the city. |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed