|

Gaze at the constant stream of romantic overland expedition posts on social media and it’s easy to believe that it’s all exotic sunsets, idyllic camp spots and laughter with locals. In reality however, it’s not all thrilling and fulfilling- overlanding has more than its fair share of exasperations and frustrations. But surely that’s part of the experience, right? Most days these provocations can be shrugged off, even laughed at, but even with the strongly developed tolerance and patience of an overlander sometimes these few repeating niggles make you want to scream from the roof(tent)tops. In this short series of blogs I retain the right to rant, expose the things that have left nail marks in the steering wheel and detail our main adventure annoyances, our overlanding irritations. So here is my stage on which to vent. First up, bad roads. Expected? Yes. Tolerated? Mostly… We’ve experienced some pretty terrible roads on our travels. Just to clarify, we’re not talking about off-road dirt tracks high up into the mountains here, we’re talking about main roads, motorways and city streets. Russia, Kosovo, Albania, Armenia, Kazakhstan and Tajikistan all have their fair share of ‘bad’ roads often with potholes larger than your car. Deep chasms are not the only surface danger, due to heavy truck traffic many roads become furrowed, once in a groove your vehicle handles like it is on rails, without a vigilant steering wheel wrestle this can suddenly send you veering towards oncoming traffic. Travelling in Armenia in your own vehicle is costly, on entry we paid at least £50 for ecology and road tax. Ironically when we left we should have billed Armenia for the damage done to our car for using such terrible roads. I’m not sure where the tax money is going but it certainly isn’t being spent on the roads. The highway system in Armenia consists of 7,633km of (apparently) paved roads, of which, 1,561km are supposedly expressways; our average speed on Armenia’s M1 was about 28mph. One of the worst stretches of urban street we encountered was in Sevan; some of the potholes on the main high street are so large you can see them on Google Earth! It is not just the road surfaces that are dangerous in these countries; the lack of road markings, signals and ambiguous road junctions are equally hazardous, as are open drain covers and deep gutters. Other potential dangers include animals, overloaded trucks and clueless pedestrians. In Georgia we narrowly avoided hitting a child, who crossing the road with his mother, ran straight out in front of our vehicle. Fortunately the only physical damage done to him was from the heavy clout round the ear his mother gave him for being so careless. Georgia’s excessive use of speed bumps is simply annoying. A motorway should never have speed bumps! Especially unmarked speed bumps.

In Western Europe we have a system for using roundabouts, it works because every roundabout employs the same system, you know your place and everybody else knows theirs. In Eastern Europe the system fails as every roundabout operates a different system. Some roundabouts allow vehicles that are approaching to have right-of-way whilst others allow the vehicles on the roundabout to have priority, some even employ both on the same roundabout. Some roundabouts even have traffic lights mid-roundabout whilst others have no road markings at all and are simply a massive city square with six lanes of traffic and a fountain in the middle. So, bad roads, the first of my adventure annoyances- the logistical network allowing me to traverse this wonderful planet, but at times my reason for breaking the 6pm G&T rule.

2 Comments

Legend has it that wine was invented 8,000 years ago in Georgia, a small country which still produces over 100 million bottles of beautiful wine varieties every year. Whilst immersing ourselves in this important part of the country’s heritage, we felt it necessary to soak up the potent grape juice with some of Georgia’s delicious array of culinary specialities and these are some of our favourites. We lost count of the Khachapuri we consumed throughout the country owing to their availability everywhere, low cost and variety. Predominantly pastry based, these hefty parcels were sufficient for a lunch or dinner snack and sold on every street in many small bakeries producing them fresh from the oven. Triangles, squares, slices, circles stuffed with melted cheese, ham, garlic mushrooms, potato, salty panir, onion… whichever you point to and pick it’s a snack lottery with a win every time. Adjaruli Khachapuri from Adjara region is a particular speciality, the pie is shaped like a boat and brimming with hot melted cheese and butter swimming round a warm, runny egg. Khinkali are the ubiquitous Georgian dumplings, the filling stuffed raw and cooked so all the piping hot juices stay inside, to be politely sucked out on the first bite. The tough, twisted top is purely for practical reasons and traditionally discarded on the plate (although then you can’t ignore how many you’ve devoured in one sitting). Filled with mixed beef and pork mince with onions and garlic, but also sometimes stuffed with herby mushrooms, cheese or potato, these delicious dough finger-foods are cheap and cheerful eats sold everywhere. For a slightly more refined appetizer, my favourite was Badridzhani Nigvsit, delicious slices of lightly fried aubergine topped with a rough, garlicky walnut sauce and decorated with pomegranate seeds. And for something sweet? Churchkhela is definitely unique to this region and looks more like a slightly mouldy, lumpy sausage than a syrupy delicacy. These odd-looking sweet snacks are a string of softened walnuts dipped in a thick, fragrant red or white grape juice and flour mixture, sometimes with honey. After the initial acceptance of such a novel taste and texture combination, chewing a Churchkela is actually very pleasurable and weirdly addictive.

Within hours of crossing the border from Turkey into Georgia the landscape began to feel more ‘wild’. Gone was the previous week’s dismay of exploring a valley only to be met by industrial development; indiscriminate scarring of the rock sides for roads and mining and rubbish strewn everywhere.

We were determined to see the beauty of the Black Sea after our motoring of the Turkish coast was disappointing with persistent torrential rain and grey skies. Sadly, a heaving great highway scours the entire Eastern Turkish coastal length; an ugly, dirty, noisy (and in most parts impassable) barrier to the narrow beaches and waves beyond. In Georgia, we arrived back at the Black Sea again just south from the port city of Poti, on the edge of Kolkethi National Park. Our camp that evening was in woodland next to a calm lagoon opposite an islet with the Black Sea beyond. As the sky flushed orange from a glorious sunset, Egrets and Herons paddled through the margins. The next morning, braving the onset of drizzle, we hired a speedboat and driver through the park office and sped across shallow Lake Paliastomi. Reaching the far side, past docile water buffalo grazing in the shallows, we manoeuvred into the mouth of the Pichori River. Motoring through reed-fringed backwaters, we passed wading birds in the Bulrushes and peatland swamps. We alighted briefly on land in the heart of the wetland relic forest, a chorus of frogs singing and wild horses padding warily through the trees. I was in binocular and field-guide-clutching wildlife geek heaven. A staggering 40% of Georgia is still covered by pristine forest and nowhere does this feel more evident than Borjomi National Park. The protected area covers an impressive 850 km2 and is strictly safeguarded to the extent that no tracks, and consequently no vehicles, are allowed in the park. We took the opportunity to swap wheels for walking, made easier by the comprehensive free hiking maps and permits to enter the park distributed by the park office and visitor centre. It was a very steep climb up muddy trails through the shady evergreen forest. We reached the snow line- the silence, isolation, crisp air and mist creating an atmosphere in which we felt we may stumble across one of the parks 90 native brown bears in every clearing. As the fog cleared, the panoramic views from the summit across the Lesser Caucasus and into the Likani valley below were breath-taking. Eagles soared level with our vantage point, dew-covered spring flowers doted the grass hillside and vibrant orchids poked from the mossy forest floor. Our route towards Russia took us through another protected area, this time through the high mountain range of the Greater Caucasus and into Kazbegi National Park. A combination of high-altitude passes through forest, windswept alpine pastureland and rocky valleys produce magnificent scenery around every twist and turn of the dramatic roads and trails. The snow-covered peaks towered above us as we set up chilly camps alongside clear, gushing glacial rivers in remote high valleys. Wildlife here is well adapted to the harshness of the terrain but excitedly, within the first day, I had the pleasure of spotting several rarer bird species within the gorges and rocky Mountains. The Georgian agency of protected areas successfully manage these wild places; wildlife protection quite rightly has priority with strict management of access and activities. Eco-tourism is well established yet minimal and without detracting from that ‘wilderness’ feel. Carefully implemented infrastructure along the trails includes visitor’s centres, marked trails, maps, camping areas, overnight shelters, campfire pits, springs and picnic spots. I have only talked about a few of the many protected reserves and parks in Georgia, 10 of which have developed marked trails. I was so impressed by how well they’ve achieved creating the balance of organised, well-designed, minimal eco-tourism development with genuine conservation.

Arriving at 5am in pitch blackness, I followed the mist-shrouded path by torchlight, the sound of singing greeting me as I opened the church doors and stepped inside. Jikheti Church, hidden in the dense forest hills of Georgia’s Guria region, was atmospherically lit by candles. I assigned myself a high-surrounded wooden pew at the far side; a prime front row view of proceedings but possibly one above my rank as I then noticed the younger nuns perched uncomfortably on small hard stools at the back. Nuns shuffled around the church in black robes and veils. Relieved at my foresight to wear a headscarf, I hadn’t predicted the unsuitability of combat trousers so was kindly issued a wrap-around skirt for decency (coincidentally in Khaki which complemented the adventure chic look). My inner feminist silently protested that the man also in attendance was wearing ill-fitting, tatty sportswear trousers which surely any god would find more offensive. I was also wearing two pairs of pyjama bottoms underneath said trousers, less of a respectful gesture and more because a stone church in the Georgian foothills at 5am in April is not the warmest of places to be sitting for long periods of time. Candles were glowing from underneath portraits of saints adorning the walls, causing the gold paint to shimmer and halo’s to glitter. As nuns and monastical congregation members entered the church, they would genuflect towards the altar then kiss and place their foreheads gently on several framed portraits and the carved wooden panelling. A nun stooped over a wooden lectern and unwaveringly recited verses from the bible, barely pausing for breath and reading each line perfectly and melodiously by candlelight. Similarly, nuns sat around the room followed the words unfailingly by the flickers of their delicate beeswax candles. A deep, man’s voice boomed from behind a carved white stone altar piece at the front of the church, immediately followed by a beautiful melodic singing from the nuns, the church echoing with their harmonious response. I copied the nearby nuns and stood up politely during this recital however, now the foremost person, I was not able to see when I should sit down again so subtly strained a look from the corner of my eye and listened for the creaking of wood as pious bottoms rested back on benches. Nuns ushered around the shadowy room, busy with lighting candles, appearing from hidden nooks behind concealed wooden panel doors. A table was carried by two younger nuns into the centre of the church and items of food were carried through the heavy doors and arranged neatly on top. Large loaves of bread, cake, bottles of oil, flasks of water, jars of preserved apricots and a bottle of wine (too early surely, even for me?). I assumed this was a ‘breakfast blessing’ as more thin beeswax candles were arranged on top of this sanctified buffet, conveniently wedged into bread rolls. The faint blue light of dawn appeared through the arched windows of the dome high above, dimly illuminating the encompassing fresco of Jesus with arms outstretched. Simultaneously, a chorus of birds began their own early morning celebration to the end of night and arrival of day. The simultaneous songs of praise, both spiritual and natural, strangely complemented each other in chanting and chirping unison. A younger monastic helper appeared from behind the altar hideaway first, the trim on his dark robes reflecting brightly like a high-vis safety vest in the half-light. He was followed by clearly the master of ceremonies, the ‘voice from the vestry’, a priest with a huge white beard, veiled hat and billowing cloak of pearlescent white. He swayed a grand silver incense burner, shaking high-pitched bells in time to each swing, and wafting clouds of surprisingly sweet and floral smoke behind him. He passed round the small congregation, waving fragrant vapour over each individual. I bowed my head on his approach but, curious for a close look at this wizard-like minister, I glanced up and caught his eye; he met my gaze curiously and sternly and I’m sure I received twice as much holy smoke as everyone else. The high priest stepped out of both church doorways and wafted the incense smoke into the cold, foggy morning air. He then retreated back into his sealed off sanctuary, through another concealed door of a life-size saint painting. An older nun approached the altar carrying a large book and, skilfully balancing a candle at its corner, dutifully recited several passages. The loud bells from the tower above rhythmically chimed bong… bong-bong… bong… bong-bong, joined in a unified chorus by a rhythmic shaking of ceremonial bells. Reappearing once more, the younger assistant carried a heavy wooden lectern to centre-stage and the high priest began reading from a thick book. After two mesmerising hours I slipped out of the side door when, almost ready to hit the road, Nino, a nun who spoke English, came to our camp outside and kindly invited us for breakfast. A table had been lovingly laid-out specially for us; the nuns follow Jerusalem time so were not due to eat for another couple of hours. The dining room contained long, wooden tables and benches, the surrounding walls beautifully painted with religious murals including an entire wall behind Andy depicting the last supper. I consider myself a spiritual person in a non-religious way, personally a resolute non-believer in higher beings of creation and afterlife. I am however always emotionally moved by services of worship and forever fascinated by the peaceful beauty, ceremony and traditions of churches, mosques, synagogues and temples. To witness this daily dawn ceremony of worship, duty and servitude was a privilege. To be welcomed to stay and share breakfast with these, often mysterious and isolated, female monastical communities, was an absolute honour and a memory I will cherish forever.

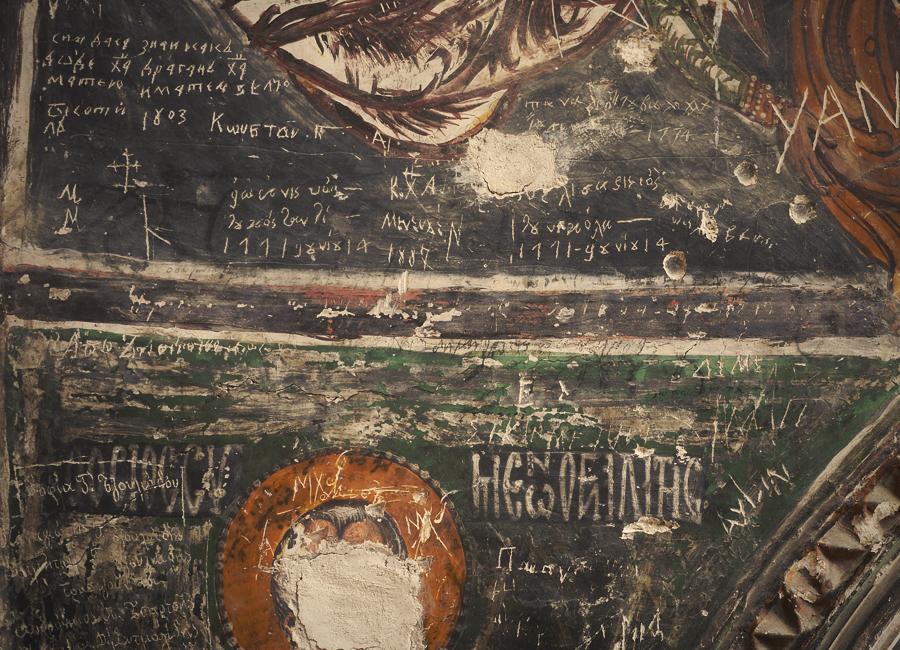

A lasting memory of Armenia will be the warmth of the people we met there, we were welcomed so many times into people’s homes and spent many memorable hours sharing food, wine, cognac and oghi (the latter not so many memories of!). On one misty morning, we set off from Kapan for a days adventuring with our new friend David in the mountains of southern Armenia’s Syunik province. We explored the villages and landscape of Shikagogh nature reserve, a beautiful, remote expanse of 100km2 of untouched forest. We stopped in tiny Tsav village and were welcomed by David’s brother in law and his family to join them for lunch. We were met with a feast of local specialities and homemade dishes including Zhingalov Khats baking on the hot metal of the wood-burning stove in the living room. Clinging to a rock face, nestled high up on a steep cliff in the Pontic Mountains in the Altındere National Park, Turkey, is the 4th century Sumela Monastery; a site of great historical and cultural significance. Having already visited the Monastery of Ostrog (Montenegro) and the spectacular Metéora complex of Greek Orthodox monasteries, both of which are perched precariously in isolated places, we were aware of the tradition typical of inaccessible Monasteries throughout the region. The remoteness of such sites meant that the monks were often safe from invaders; they believed the altitude bought them closer to god and the servitude involved in the construction of such remote structures surely secured them a seat in heaven? With such solitude these beautiful locations are highly conducive to prayer, contemplation and meditation. They became the focus of pilgrimage; a place to turn your mind away from the distractions of the outer world and focus on discovering the profound truths of the inner world. For over 1,629 years a monastery of some description has endured the elements on this secluded spot in Northern Turkey 1,200 metres up. During its long history the monastery has fallen into disrepair several times, then consequently restored by various emperors throughout the ages. It was around the 13th century that this existing incarnation (including the frescoes) was formed during the reign of Alexios III. During the Ottoman Empire the monastery was granted the sultan's protection and given rights and privileges that were renewed by following sultans protecting it for many decades. During the 1916-18 occupation of Trabzon the monastery was seized by the Russian Empire, then in 1923 the site was abandoned during the Turkish War of Independence. Today the monastery is open as a tourist attraction; despite its cultural and religious significance the site draws in curious visitors who marvel at its location alone. Unlike the perfect frescoes we witnessed at Decani monastery, the frescoes here have endured years of weathering, as well as vandalism during the times that the monastery was abandoned. At first glance the vandalism my seem unthinkably sacrilegious but on closer inspection un-digestible layers of scratchy scrawl engraved on the surface reveal a fascinating insight into the monasteries history. Who was Nebile Okur and what was he doing here in 1970? But it’s not just modern day graffiti, look a little harder and you’ll notice earlier and earlier dates; 1964, 1952, 1911, 1899, 1878, 1833, 1803, 1774, 1762 and the earliest we spotted 1511. The names and dates here document the times that are often unaccounted for by the history books. Like many of the Frescoes in the Göreme cave churches we visited in Cappadocia the eyes and faces on the paintings have vanished. It is said that the eyes are often worn due to pilgrims touching them. Some say that the faces were often chipped off by people wanting to keep a souvenir of their visit. The frescoes of the chapel were painted during different periods; in places the newer layer has been completely removed or fallen off revealing the previous frescoe which has been systematically chipped for the new layer of plaster to adhere to. Sumela monastery is a marvel from both outside and in; externally, the sheer devotion of its construction and breathtaking position in the landscape. Internally, within the crumbling and restored walls, echo stories over the millennia of prayer, devoutness, safety, war, sacrifice and a restored feeling of peace and optimism for the future.

It was a cold, grey, drizzly day in Niksar, Turkey but as the door to the household kitchen swung open we were met with two kinds of warmth; that of the wood burning stove blazing in the corner and the welcome friendliness of a Turkish family. Having met our campsite owner, Tunay, only the previous day he had proudly embraced the visitors to his home town and invited us to eat with his family the following day. As is often the way with home-cooking, the mix of dishes was delectably different from the occasional kebab street-eat we had sampled so far across Turkey. ‘Çay’ is the staple throughout the day- black tea sipped from small, tulip-shaped glasses with plenty of sugar. The tea kept flowing, topped up from a double teapot on the stove; strong black tea from one spout and hot water from the other.

We frequently encounter such hospitality, warmth and openness from people in foreign lands, an unforgettable experience and fond, lasting memory.

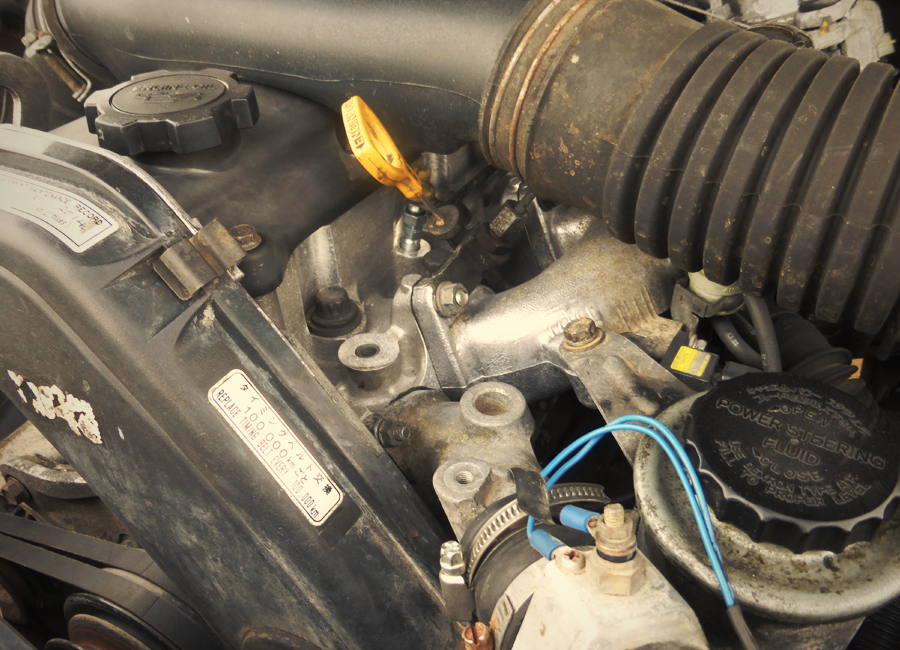

After a short hibernation period were about to head back out on the road. Bee-bee’s cracked cylinder head has been replaced and she is raring to go (we hope). Here’s a quick outline of the work she’s had done... New Cylinder Head

Water Pump

Radiator

Cam Belt, Glow Plugs and Fuel Injectors

Having racked up over 150 test kilometres I’m pretty convinced she’s running sweeter that she ever has. She starts on the button, no more black smoke and the temperature barely rises above 88°C. We took her (unloaded admittedly) on several long motorway climbs and up a steep 290 metre off-road climb without any problems at all. Fingers crossed.

What was that bang?

At first it seemed like Bee-bee had just overheated and popped the top off the expansion bottle. We let her cool down and refilled the radiator. We tried to start the car but got nothing but a ‘clunk’. Andy thought the starter motor might be jammed, we rocked Bee-bee backwards and forwards (for sympathy and to hopefully un-jam the starter motor). A turn of the key and she sprang back to life in a huge cloud of white smoke. It was at this point that Andy declared that we’d probably blown the cylinder head and that water had leaked into one of the cylinders which became ‘hydrolocked’. We sloped on cautiously towards the next town in a cloud of white smoke. Stuck in Kumluca

Frantically searching the Hilux Surf forum for advice on what he suspected, Andy declared he was “95% sure the Head gasket had blown”. Aside from a crash, this was one of the worst things that could happen to our car (mechanically and financially). We had 48 hours to get us and a broken car 301.43 miles (485.10 km) to the Port of Tasucu where a non-refundable ferry was due to take us to Cyprus. As with every tragedy there are the heroes and villains; our hero was Alim the hotel manager’s son who spoke English, understood our predicament and arranged for some tow truck people to come in the morning. The unfortunate villain was the waiter in the restaurant who informed me they didn’t serve alcohol. Tow Truck (Wheelin' and Dealin')

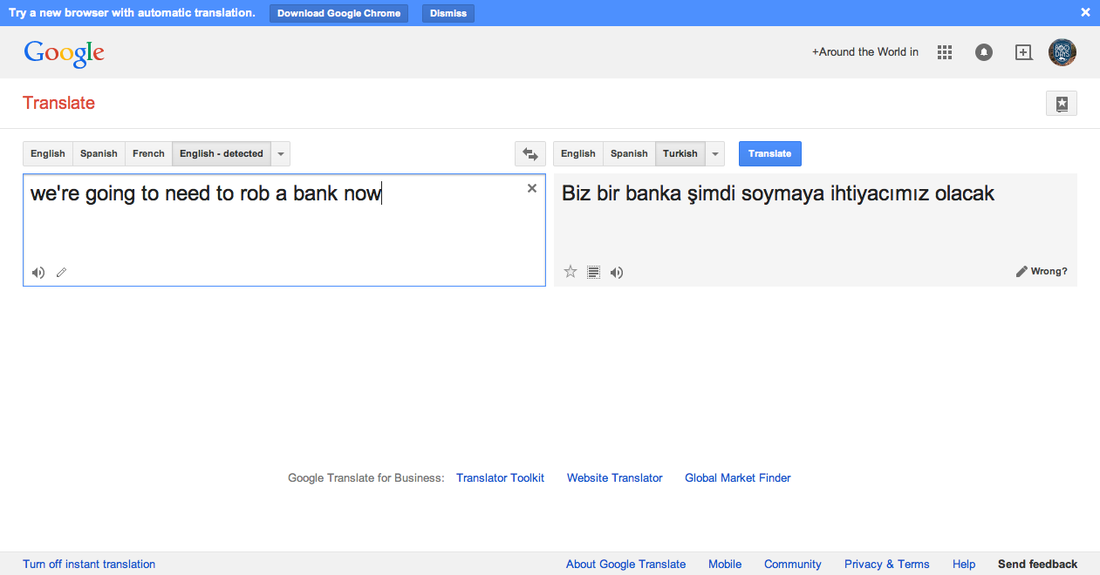

The final computer translation told them we were off to rob a bank. Ironically, when Alim took us to the cash point I sat in the back with a shotgun under my feet. I assume that was a normal item in a car here and he understood we were joking about the bank. I didn’t mention it. Tow Truck 1 - Ugel the Rally Driver

Tow Truck 2 - Mustafa the Redbull Racer

We spent about 2 hours in a smoky (but warm) station office with a Turkish soap opera on TV in the corner. A car of oily youths arrived with a few ‘new’ alternator options and scrambled about systematically until the truck roared into life again. Mustafa necked 2 cans of Redbull. We were off. We Drove All Night

17 Hours in Tasucu Port

We walked back into town (not daring to ask for a lift). During this time we must have set a local record for number of teas drank. We were exhausted and cold, we rooted at a friendly local café, ordering small dishes with lengthy interims to justify our temporary residence at their table. When it eventually went dark we bussed our way back to the Port but were stopped at the customs gate where we spent another hour dozing in chairs with bored customs officials in their office. Eventually they let us have access to Bee-bee (if we ran through the port and no one saw us). We popped the tent subtly, sandwiched between rows of lorries and lay down for an hour. All Aboard The Lady Su

Crossing the Cilician Sea

He beckoned us over to come up so we made our way through the ships corridors, stepping over piles of broken furniture and tools, up onto the ships bridge. Muhammed, the lone Captain, seemed to appreciate our company up on the bridge- he gave us bananas and told us that the boat had to be registered in Sierra Leone as it would never have passed strict Turkish health and safety regulations. Docking in Girne

Across Aphrodites' Island

The DiagnosisThe devastating news was what we expected; the cylinder head was cracked in two places. |

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed