|

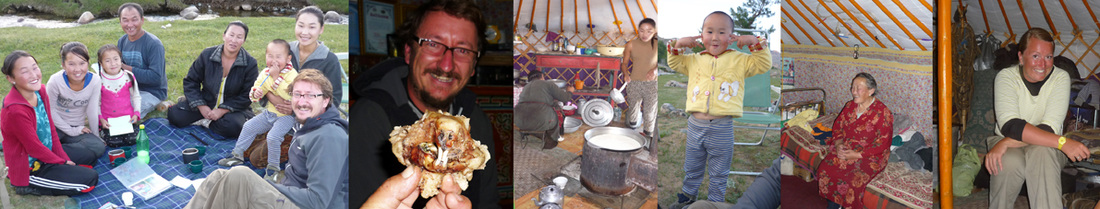

With a perfectly-pitched camp on the banks of the Zavkhan River overlooked by the holy Otgontenger mountain, dinner was underway (tinned sardines despite two hours spent fishing for Taimen giant trout in the river) when we spotted a small army of Mongolians approaching from the South. Sardines off and tea on, the mother and children gathered on a blanket, entertained by our phrase book and photo album while the father meticulously independently surveyed at, in and under our car and rooftent. The family comprised of parents, four daughters aged 15, 12, 12 (twins, bizarrely with the same name), 10 and a son of 4 years. They were staying at their grandparents nearby Ger and had been dispatched on a mission to locate the occupying foreigners and instigate a peaceful surrender, detainment and imperative retreat to their circular abode. A stoop of the head through a painted, decorative doorway transports you into the rotund hive of all Mongolian nomadic activity. The Ger, a felt-lined wooden-framed tent-like structure is still home to just under half of the population of Mongolia. Even amongst families which have now settled in urban areas, a third of these still live in Gers rather than houses (something we witnessed in ‘Subgerbia’ areas on the outskirts of towns). This spherical, transportable, dwelling was crammed around the edges with the couples entire possessions, both decorative and practical. Kitchen equipment, pots, pans and stashes of food provisions sit snugly next to beds, boxes, blankets and a modest Buddhist shrine. On the walls are photos of family members and a treasured collection of the grandfather’s horse riding medals alongside framed pictures of Buddhist deities and famous Mongolian folk wrestlers. At the base of the central yellow wooden support pole was a metal stove burning away, on top of which a large, shallow silver bowl of yaks milk steamed as the grandmother stirred it dutifully. Two tin cups were produced and dipped into the rich milk for both Andy and myself. This was followed by a ‘slice’ of Yak clotted cream skimmed from the boiled milk’s surface, and a warm, salty, weak milk tea decanted from a flowery, fluorescent cork-bunged thermos flask. To accompany the tea, a bag of biscuits were produced; at first glance a sweet treat but on closer inspection a greying delicacy with blue mould spots on one side. The first bite revealed the pungent flavour of musty, fetid goat’s cheese. The second bite was only marginally better due to the lack of expectancy of shortbread rather than the reality of rancid, crumbly goat product. But this array of calorie-crammed, creamy dairy delights was, unbeknown to us, just the starter. A grubby, battered metal dish was extracted from under one of the wrought iron beds that formed the periphery of the Ger. The bowls contents were the result of a recent rodent genocide; those cute, curious marmots we had witnessed regularly skipping across the path ahead of us or popping up like a periscope from their burrows had been reduced to a greasy, gruesome goulash of flesh and fat. Would we like to try some? Of course we would! Sensing our trepidation with consuming something that looked more pet than picnic, our host pot-rummaged and produced the full boiled head complete with greasy flared nostrils and perfectly intact, protruding buck teeth. He waved it in the air like a ceremonial severed snack much to the raucous amusement of the rest of the family. After rancid cheese biscuits this cold, slimy flesh was actually quite palatable. Andy went back for seconds. A plastic bottle not too dissimilar to the ones that white spirit is sold in was produced from another corner of the Ger with the father proudly announcing “vodka” before filling a tin mug full of the colourless liquid for Andy. This was ‘Airag’, fermented mares milk, fortunately only around 5% proof but unfortunately also allowing for clear enough thought as to how exactly you milk a horse. The atmosphere in the Ger became animated as the women imitated a drunken Andy trying to climb up the ladder into the rooftent following consumption of this equine homebrew. By this point grandfather had retired noiselessly into his bed but his family continued to chatter enthusiastically. Communication is beautifully basic; an antiquated English grammar schoolbook, a hesitant jumble of gesticulations and actions, illegible sketches and simply smiles. The warm generosity and hospitality of these complete strangers and the genuine welcome into their home was extremely humbling; an experience which we will forever cherish in our memories (and one which took our stomachs a few days to forget).

Emma

2 Comments

|

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed