|

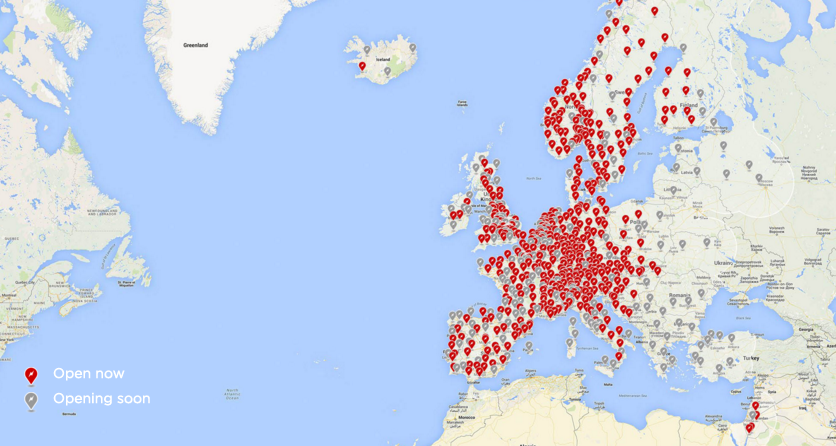

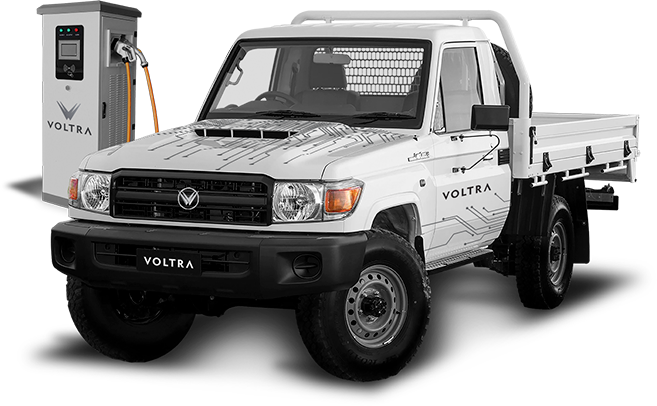

Since our last adventure most of our time has been spent trying to save the planet and the eco-systems we so dearly love and rely on. As every day passes the severity of the climate emergency we are in becomes more and more apparent. We dream of visiting the Amazon rainforest, but we fear that by the time we get there it might be gone! Every action has a carbon cost attached to it, which is making decisions very hard to make. Should we even continue our trip? Will we feel huge guilt by doing something so selfish when we should be fighting for the planet? How will we get to South America? Do we need to stop using Bee-bee because she runs on diesel? Is it feasible to use an electric 4x4 to overland the world? In this blog I’m going to focus on that last question. Is it feasible to use an electric vehicle to overland the world? The simple answer is yes. In 2017, our friends, Magdalena and Benedikt were the first to circle the Caspian Sea in an electric vehicle (Tesla Model S), from Switzerland to Central Asia and back via the Baltic countries. The “official” charging points finished in Croatia, forcing Magdalena and Benedikt to get “creative” adding a new dimension to an already tough overland trip. I had the pleasure of designing the vehicle graphics and interviewing them on The Overlanding Podcast. On the 7th of April 2019, The Plug Me In project finally reached Sydney from the UK after travelling for 1,119 days through 34 countries, covering 95,000km becoming the longest journey in an Electric Vehicle to date. So… It is possible, but... Is it greener to replace Bee-bee with an electric alternative? To calculate the carbon footprint of any vehicle is incredibly complex. The processes involved in getting raw minerals from the ground and made into a showroom ready vehicle are multifaceted and include many separate industries. Components have to be produced and often transported and then assembled. Every stage of the process requires energy and produces carbon, including the production of buildings and infrastructure (robots, phones, desks, etc). Once the vehicle has been built, the way it is used, how old it is and how well it has been maintained are all wildly erratic variables that affect the amount of carbon it produces. Luckily someone else has done most of the hard work for me. In his book “How Bad Are Bananas” – Mike Berners-Lee concludes that most new vehicles have a carbon footprint that equates to a monetary value. Berners-Lee suggests that a new vehicle will have a 720kg per £1000 that you spend on it. Unfortunately our vehicle isn’t new. Bee-bee is 26 years old and has a 3-Litre Turbo Diesel engine that has been well maintained. Typically, embodied emissions produced in the production of new cars equal the exhaust pipe emissions over the entire lifetime of the vehicle. Bee-bee is older than average. Berners-Lee deduces - “Generally speaking, it makes sense to keep your old car for as long as it is reliable, unless you are doing high mileage or the fuel consumption is ridiculously poor.” Essentially the longer you keep your vehicle the more the embodied emissions reduce per mile over time. On top of the Carbon produced by burning the fuel there is the carbon cost of getting the fuel out the ground, refining it and then shipping it around the world. Diesel engines are typically about 30% more efficient at turning fuel energy into vehicle movement. Unfortunately for us, each litre of Diesel has a slightly higher footprint (13 per cent) than petrol, but it produces a proportionately higher energy to compensate. Typically petrol is a cleaner option. Sadly diesel engines produce higher levels of microscopic particulates and nitrogen oxides and contribute massively to reductions in air quality that effect humans. These ultrafine particulates can penetrate deep into the lungs, causing irritation and can potentially trigger asthma attacks and cancer. According to Berners-Lee “Overall, it is hard to say which fuel wins as the environmental vehicle fuel”. What we do know is that both petrol and diesel are pretty terrible for the planet, with diesel being worse for humans. How does that compare with an electric vehicle? If the production of the vehicle produces about 50% of the total carbon footprint with exhaust pipe emissions making up the other half, does that mean that 50% of the total carbon footprint of an electrical vehicle is tied up in the production too? No, is the simply answer. Electric cars use lithium-ion batteries. The extraction of the exotic materials (lithium, cobalt, magnesium and nickel) used to produce those batteries creates hotspots in the vehicle manufacturing process. In a head-to-head comparison, electric vehicle production generates about 97% more carbon than a traditional combustion engine, with about 43% (the hotspot) of that being the battery. As technology advances these figures should reduce. Electric vehicles are charged by coal, gas and nuclear power stations, as well as some renewable sources, all of which have an associated carbon footprint. So that raises the question – how much of a carbon saving does an electric vehicle actually give you? Well thankfully, again, someone else has done the hard work for me. Volkswagen (who can definitely be trusted when it comes to telling the truth regarding emissions) carried out a like-for-like cradle to grave comparison between a pure electric e-Golf and a diesel-powered Golf TDI. Volkswagen concluded that “even in countries that are intensely reliant on coal-fired electricity, like China, a battery electric model will always pollute less CO2 than one with an internal combustion engine”. Even with the additional carbon produced during the production of the battery the typical saving is about 15%. This would be greatly increased if the electricity used for charging was sourced from renewables. That figure came as quite a surprise to me. I was expecting it to be a much higher saving. It is pretty much impossible to come to a definitive conclusion as to the carbon saving figure we would make by switching to an electric vehicle – we simply can’t compare like for like. It would be fair to say though that we wouldn’t be adding more carbon by switching, especially if that vehicle was second-hand. You only have to have a quick glance at the Electric Vehicle World Sales Database to realise the rate at which the sector is growing. As a result of the expanding electric vehicle market (and popularity of handheld devices), the demand for lithium is increasing exponentially. Between 2016 and 2018 Lithium doubled in price. Ironically, as the world clambers to replace fossil fuels with clean energy in an effort to clean up the planet, the consequences of extracting that much lithium is becoming a major issue in its own right. Toxic chemical leaks from Lithium mines have wreaked havoc with ecosystems and it’s predicting that, by 2050, the demand for the exotic metals essential for lithium-ion batteries may be in short supply. The lithium extraction process uses huge amounts of water, in Chile’s Salar de Atacama, mining activities consumed 65% of the region’s water. Lithium is not the only problematic metal used in producing batteries. Cobalt, unlike most metals, is classified as a toxic carcinogen and has been linked to cancer. It’s found in huge quantities across the whole of the Democratic Republic of Congo and central Africa and in recent years the price has quadrupled. These factors have resulted in unauthorised mines cashing in on the demand, resulting in unsafe and unethical methods of extraction, often using child labour, without the appropriate health and safety equipment and procedures. The final issue with lithium-ion batteries is what to do with them once they reach the end of their lifespan. They are incredibly difficult to recycle. Ironically when researching this blog post I discovered two companies, Voltra and Tembo, that make an electric 70 series Landcruiser… wait for it… to be used in mines that excavate coal. It is common knowledge that the world would be a much better place if fossil fuels were left in the ground. Where’s Alanis Morissette when you need her!? “Voltra provides underground mining fleets with the durability and toughness of the original 79 series Land cruiser, but with zero emissions, significantly reducing a mine’s carbon footprint”. Being an environmentally conscious overlander is hard work. Making the correct decisions to limit your own impact on the world is a minefield of complicated sums and moral dilemmas. Is there even a suitable vehicle that could replace Bee-bee? The market for off-road electric vehicles is currently slim. Telsa announced the CyberTruck last year. One part DeLorean, one part stealth bomber, it’s not the most attractive of vehicles and where would we put the rooftent? Elon Musk claims it’ll have a +500 Mile range, he also claimed it was bulletproof. At it’s big reveal, Telsa’s head of design, Franz vol Holzhausesn threw a metal ball at the windows to demonstrate how tough it was, embarrassingly the glass broke. With a price tag of +$60,000 for the all wheel drive tri-motor version and a release date of 2022 it’s highly unlikely to happen for us! The most likely contender to populate the electric overland market is the Rivian R1. With a +400 mile range and some smart design Rivian are aiming for a market they understand. The Rivian R1 will be available as a pick-up and 7 seater station-wagon, has a wading depth of nearly a metre, up to 750hp, advanced traction control, a low centre of gravity and an incredible 0-60 time of 3 seconds. With independent motors operating each wheel it can even perform 360 degree “tank turns”. Again, with a price tag of +$60,000 and a pre-order waiting list I think we can cross this one off our list. Some companies offer conversions for existing 4x4’s. For the traditionalist, Plower in Holland can build you an electric Land Rover Defender. In Germany Kreisel can build you a fully electric G-Class.

As all these vehicles are well out of our price range we find ourselves asking the question again - Is there a suitable vehicle, which could replace Bee-bee and appease our demand to see the world with as little impact on the planet as possible? Yes… a bicycle.

0 Comments

Arriving into Thailand after a full-on, hectic four and a half months in India followed by a strict two week Myanmar guided tour we spent our first night camped in Taksin Maharat National Park near the Northwest border. The immediate quiet and organisation of the place was a shock to the system! Off season, the camp site was empty so we had an entire site for us and our French family friends in their motorhome who we’d travelled across Myanmar with. A basic yet sufficient wash block meant we had clean water, shower and toilet facilities and a huge open, flat space to clean, hand-wash, re-order (and relax) after our Indian odyssey. There are 127 National Parks in Thailand, varying from quiet, low-key areas with basic camping facilities to tourist-tastic parks complete with Hornbill keyrings and Deer tame enough to take a selfie with. They are excellent places to plan your route around as the facilities are perfect for overlanders and the cost minimal- with incredible jungle, mountains and coastline they are perfect places for relaxing in nature and spotting (surprisingly easily) many of the hundreds of species of animal, birds, reptiles and insects. Mae Surin National Park offered an escape from the steep tarmac roads, as beautiful, sedate sand tracks weave along the edges of unspoiled forest. Wild camping was easy with viewpoints and picnic spots overlooking an undulating, tree-covered horizon. Our next stop was Khao Yai National Park, in the East of Thailand, where we stayed 3 nights at Lumtakong Campsite where the less-than-shy resident Sambar Deer outnumbered campers several to one. Drinking tea with the beating of Hornbills wings flying overhead and jumping as a huge water monitor lizard strides past you, slipping into the nearby river and gliding across. Dawn hikes through swaying, orange sunlit grassland with wild elephants crashing through the undergrowth nearby and gibbons howling and acrobatically swinging through the jungle canopy above. This is the gem of Thailands Parks, with a modern visitor’s centre and over 50km of marked, extensive, beautiful hiking trails. Southwest of Bangkok, we visited Kaeng Krachan National Park, staying in Ban Krang campsite where salt licks attract huge aggregations of colourful butterflies (over 300 species!) at the camps entrance. A stream flows through, with Malabar squirrels hanging from tree branches above and stump-tailed Macaques chattering in the tree tops. Smaller, low-key reserves dot the Thai coastline, our first experience of this was at Hat Wanakon on the East coast. With our hammock slung between two beachside pine trees we watched a stunning sunset over the water as fishing boats bobbed past. In the morning we wandered through pine groves, large vivid lizards diving for their burrows, on our way to the outdoor showers. Crossing the narrow band of Southern Thailand to the West coast we camped at Laem Son National Park, fringing an idyllic stretch of beach with forested outcrops. Khao Lampi Hat Thai National Park further south boasted a completely empty campsite, beautiful solitude right on the beach- coastal wilderness with the luxury of toilets and showers in a scenic pine forest. Karst limestone islands loom from the waves in Krabi province, creating a surreal landscape around Hat Chao Mai National Park. Along this deserted stretch of beach on the Andaman coastline we saw no one but the odd curious cockle collector and were able to swim and sunbathe in peace with the tide lapping all the way to our table and chairs. Timing is key when visiting Thailand’s National Parks; they are far more enjoyable when quiet so try and visit off-season if possible and during the week. The bigger parks have a reasonably budget-denting entrance fee (eg- Khao Yai is £8/$10 each) but this covers your entire stay, no matter if you visit for an afternoon or four days. We chose fewer parks but stayed longer to make visits more economical and give ourselves enough time to relax and hike the surrounding area. Camping is extra but only around 60p each a night and the facilities are basic but generally well-maintained. In contrast the smaller coastal parks charge only £2/$3 entrance so you can afford to stay in several for single nights. The security of patrolling rangers on campsites means you can stay ‘set-up’ and wander off into the wilds and sleep better without that ‘on-guard’ feeling when wild camping. Of all the countries we have travelled in, Thailand’s National Parks are by far the best, managing to maintain that wonderful wilderness feel while providing fantastic, affordable facilities across the entire country. It’s a great way of seeing wildlife while contributing directly to its protection.

Only a few kilometres from one of the worlds most visited monuments, The Taj Mahal, lies the Agra Bear Rescue Facility on the peaceful Yamuna River. The centre houses and cares for 211 Indian sloth bears, all rescued from the horrendous former practice of ‘dancing bears’. Historically, Indian Sloth bears cubs were stolen from their mothers, their muzzles pierced with a red-hot iron poker and a rope attached through their nose to force them on to their hind legs to ‘dance’; first for Mughal Emperors, then for local crowds and tourists. The bears endured a life of pain and suffering with health problems, cramped cages and poor food. In 1996, research carried out by the non-governmental organisation Wildlife SOS revealed 1,200 dancing bears in India. Over the next 12 years, Wildlife SOS achieved the incredible task of rescuing and rehabilitating more than 600 bears until the last dancing bear was rescued in 2009. We had a tour around the rescue centre in Agra, where groups of rescued bears roam in large enclosures, each group cared for by dedicated keepers. Their health is continually monitored as years of abuse and malnutrition, plus the physical scars of their nose piercings and canine teeth removal can cause them ongoing problems. In a sad reminder of their past lives in servitude, their noses still show tears and holes where their ropes were tied and some bears still sway repeatedly, still haunted by years spent in confinement. A visit to one of the centres two kitchens revealed the enormous scale of feeding over 200 large mammals; huge vats of wheat and millet porridge with honey and milk sat ready to be distributed to the bears for one of their three daily feeds, alongside boiled eggs, fresh fruit and cooked vegetables. It was amazing to watch these majestic animals, finally free from their lives of painful performance and torture, now able to enjoy social interaction, good food, natural behaviours and a life in peaceful nature. It’s an incredible success story for conservation and animal welfare in India and demonstrates what can be achieved in a relatively short space of time by dedicated and passionate individuals Kartick Satyanarayan and Geeta Seshamani and their team. Volunteers from around the world come to the facility to give their time to help feed and care for the bears, as well as raising awareness and much-needed funds for the ongoing work of the organisation.

Despite the trade in dancing bears being over, the threat of poaching of Indian Sloth Bears still remains. We met ‘Elvis’ who was recently confiscated on the border with Nepal on his way to China where there is still a lucrative market in bear ‘parts’ for medicine. Fortunately he was rescued in time and is now in quarantine at the centre where he is doing well. You can visit the Agra Bear Rescue Facility and even arrange to spend a day with keepers to learn more about their work caring for the bears; http://wildlifesos.org/agra-bear-rescue-facility or follow their fantastic work with wildlife on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/wildlifesosindia The natural beauty of Kyrgyzstan is simply overwhelming- varying altitudes create a huge diversity of landscapes, with alpine valleys, flower meadows, snowy mountains, fertile pasturelands and fast-flowing clear rivers vying for your adventure attention. For us, one of our lasting memories will be the aquatic gems which lie amongst its mountains, notably our three favourite lakes; Issyk Kul, Song Kul and Sary Chelek. Issyk KulBeach. Serene. Relax. Meaning ‘Hot Lake’ in Kyrgyz, Issyk Kul is the world’s tenth largest lake (by volume) yet never freezes, despite the shores reaching sub-zero temperatures in winter. Wash your car in the water (as we foolishly did!) and the white, oily sheen left over the entire surface reveals its anti-freeze secret- a low level of salinity. In fact, it’s the second largest saline water body in the world, after the Caspian Sea. Only two and a half hours drive from the Kyrgyz capital Bishkek, this is the perfect escape from the city and in the summer is visited by thousands of Kyrgyz holidaymakers and Kazakhs from across the nearby border. Your personality dictates your shore preference- on the North you can pedalo and party with fluorescent beach resorts pumping out distorted Russian pop amidst the lingering smell of mutton shashlik and Baltika beer. Meander along the south and you can find entire, sedate beaches to yourself or wander into the quiet backdrop of mountains into Swiss-like scenery with crystal clear rivers and lush green valleys. At times, driving along the South coast the blue waters and sheltered rocky coves and beaches are reminiscent of an azure Adriatic coastline. We visited alluring Issyk Kul three times, driving a complete lap on our first jaunt, diverting into several valleys with mineral springs, glacial rivers and grassland plateaus and visiting the charming market town of Karakol. Our second stop-off, on route back from southern Kyrgyzstan escapades, was more relaxed with a few days camped on a quiet stretch of the northern shore, swimming and watching the sun set across the water over the Tian Sian in the distance. Finally, when prolonged visa delays in the capital became too much, it was to the southern shore of Issyk Kul that we fled, the lapping waves bringing instant calm and lazy beach days rejuvenating our stressed souls from permits and paperwork. Song KulRemote. Wild. Elemental. The loftiest of the lakes at just over 3,000m, Song Kul leaves all the beachgoers and picnickers at the foot of its perilous road and high-pass precipitous approach, almost an initiation for those worthy enough to make the effort and reap the rewards of time spent in this incredible location. This is true wilderness; a remote and barren place where the weather changes in an instant and the sky is a rolling, dramatic aerial dome of colours and clouds. A lap of this far-flung lake is an off-road expedition on steep sand tracks, through boggy margins and stony beaches, passing isolated yurt camps and windswept plains. During our summer visit, the northeast part of the lake was home to nomadic grazers; their numerous sheep, goats, yak and horses dotting the rich grassland. Friendly nomads called at our camp, joining us for tea or breakfast and insisting we ride their horse in return. Young, pink-cheeked children practise herding, bouncing around on donkey-back and giggling as they stop to let their mini-steeds drink from the lake edge. Sary ChelekVerdant. Lush. Picture-perfect.

A diversion into western Kyrgyzstan and a bumpy climb through the lush forests of Jalal-Abad Province is rewarded with the picture-perfect sight of Sary Chelek Lake. Nestled between vertical forested slopes of the Chatkal Mountains, the colossal snow-covered peaks of the Tian Shan loom in the distance, reflected enchantingly on the still surface of the water. A relatively small lake compared to its mightier cousins, at just 1.5km at its widest point and 7.5 km long, Sary Chelek translates literally to ‘yellow bucket’ after its appearance amidst golden trees in autumn. In contrast, our summer visit was a green vision of verdant beauty. Winding steeply along the approach road, an occasional peek of the vivid blue lake is glimpsed between the dense, overgrown vegetation and woodland. The inaccessibility of the lake protects its pristine relict fruit and nut forest edges, we settled for a camp on the shores of a nearby lower lake connected by shallow cascades. This is a shared paradise with many other visitors but we managed a quiet afternoon paddling in the cool edges, watching shoals of fish darting in the shallows and relaxing in the lakeside meadow. The true heart of Kazakhstan can be found in its vast steppe land, at times stretching to an infinite horizon in every direction. The world’s ninth largest country, a third of Kazakhstan’s colossal land area is steppe, an indication of just how immense this landscape is. So common is the sight of eternal, flat plain that it is easy to take this beautiful habitat for granted and many exploring the natural wonders of the country bypass this glorious grassland and focus mainly on its mountains, canyons, lakes and National Parks. At first sight, the steppe landscape can appear monotonous and barren but peer closer to the ground and there is a myriad of wildlife to be discovered. Hot, dry summers and freezing winters present challenging conditions for survival, but the species that can be found here are perfectly adapted to the extreme fluctuating conditions of drought, strong winds, frost and grazing. In the remote, northern regions of the country driving distances are huge and harsh road conditions make overland travel laboriously slow and bone-shaking. A bumpy journey weaving around potholes with little other traffic does have the one advantage of offering the chance to view many steppe species surprisingly close-up. Bobak Marmot relax stretched-out in the sunshine on road verges, lazily watching you swerving past. Around our campsites these stocky, ginger-coloured rodents stand on their hind legs from their sandy burrow entrances, watching you cautiously and scurrying deep underground, squeaking, should you get too close. The diversity of birds of prey on the steppe is staggering; Eagles, Kites, Buzzards and Kestrels soar and perch every few hundred metres. White Pallid Harrier hover ghost-like over the road verges hunting for mice while magnificent steppe Eagles sit poised on tree stumps surveying the horizon. We camped wild across the steppe for the entire month of May, a wonderful opportunity to experience spring in Kazakhstan. With a completely flat horizon, the sky presents a ginormous aerial auditorium to view the fast, ever-changing weather patterns which roll in across the landscape. Standing in one place, you can see black clouds with sheets of vertical rain pouring down, flashes of fork lightning and hear rumbling thunder in front of you. Behind you is bright blue sky, white fluffy clouds and brilliant sunshine. One minute we were setting up a picnic in the sun, then 5 minutes later diving for cover of the car as huge icy hailstones battered the earth. Tall, elegant steppe Hare leap from nowhere as you search for a camp spot, bounding ahead effortlessly along the grass track. Small, charming ground squirrels peep from their burrows, waiting until the last second to dive out of your way, inquisitively reappearing minutes later to see what’s happening. In the warm light of sunset the carpet of tall grass swaying in the breeze turns golden and the songs of thousands of insects are amplified as the light fades. At dusk, bats swoop from nowhere and the cautious rustlings of small rodents can be heard emerging from burrows nearby, tiny voles wide-eyed when caught in our torch light. At dawn a new chorus begins as incalculable bugs welcome the arrival of day; butterflies flitting amongst the flowers, vivid, hairy caterpillars climb the tall stems, ants march across the dry soil, bees buzzing between poppies, iridescent beetles clinging to tall grass tips and crickets and grasshoppers leaping in all directions with every step you take through the meadow. For all the beauty and magnificence of National Parks, it is simply unbeatable to wake with the sound of a cuckoo calling, crickets chirping and an unobstructed 360 degree view of wild expanse, often without any sign of people or buildings. Though gentle and delicate to look at, not even the might and power of a crushing soviet offensive on these peaceful pastures could tame their roots. During soviet times in the 1950’s, a vast majority of the Steppe was brutally ploughed and planted as far as the eye could see with cultivated wheat fields, with only around 20% of the original steppe preserved. Agriculture failure was widespread and has been abandoned in much of the steppe, where slowly the grassland is regenerating and nomadic pasturing has returned.

|

Archives

July 2020

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed